|

|

04/08/2014 |

Click here for Part 1 and the introduction to this series. Click here for Part 1 and the introduction to this series.

Mortise chisels as a special named category of chisels date from at least the mid-17th century. Moxon's "Mechanick Exercises" has both a drawing and instructions for chopping a mortise using them. However, most of the specific information that we have on mortise chisels (actually on most tools) comes from old tool catalogs. The earliest tool catalog with illustrations is "Smith's Key" from 1816. Engravings of tools at the time were very expensive and "The Key" is a generic list of illustrations that any manufacturer or distributor could pair with a price list to show the customer what they were getting. This worked because while there were differences in minor details of quality and fit and finish, by and large all the tools of a type from Sheffield were basically of the same design. For example in this photo, these two very late 18th century or early 19th mortise chisels by Joseph Mitchell and Phillip Law, both Sheffield edge tool makers, are essentially the same and in theory could even have been actually made for each company by the same actual craftsman. The modern reprint of "Smith's Key" is bound in with a rare, actually unique price list listing the tools in the key and their prices from James Cam, another Sheffield manufacturer. The best guess anyone has is that the price list dates from at least five to as much as twenty five years after the list was originally printed. This gives you a good idea of how expensive the engravings were duplicate at the time.

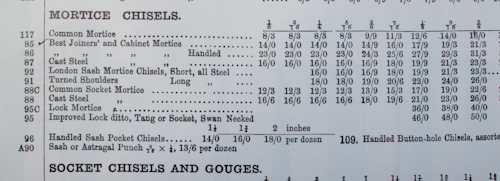

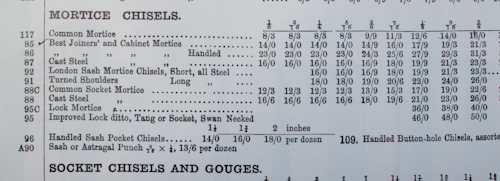

All the catalogs I consulted list the following options: "Mortice Chisels", "Best Joiner's Mortice Chisels","Best Cabinet Mortice Chisels", and "Socketed Mortice Chisels". By 1884 the James Howarth catalog also lists "[Solid] Cast Steel Mortice Chisels" and "Best Joiner's Chisels - Handled". Also listed in that catalog are "Sash Mortice Chisels".

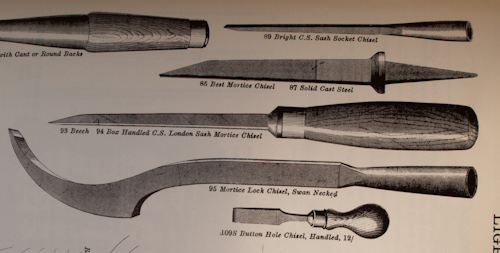

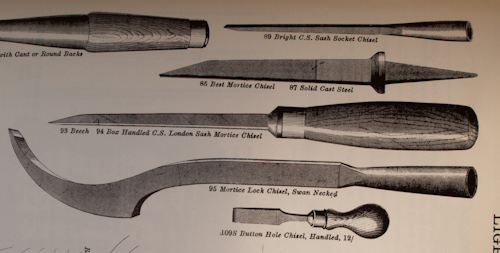

"Socketed Mortise Chisels" are really heavy, have a giant socket (not like the demure sockets of the 20th century Stanley 750 derivatives), and are too rough and rare to be a viable chisel for people to used for general mortising.

"Sash Mortise Chisels" are shorter, lighter, and ground parallel. They arrive on the scene in the 1850's era, are tanged, with a ferruled handle. They are very handy for doing the shallow mortises needed in window sashes, but are downright frustrating to use on full size mortises.

It's the first three types of Mortise chisels that are of interest to us today. "Mortice Chisels", "Best Joiner's", and "Best Cabinet" all have tapered oval or (sometimes on very early samples) octagonal handles that butt up against oval, octagonal, or semi-oval bolsters (for an illustration defining these terms see part one of this series). The early versions (mid-18th century to early 19th) might have octagonal bolsters but the overwhelming survivors have oval bolsters of one quality or another. A fair number of the earlier mortise chisels I have have squarish bolsters that were rounded off without being actually oval.

Other than the illustrations I don't know of any contemporary distinction between these three types of chisels. The price between the regular mortise chisels and "Best joiner's or cabinetmakers" is nearly double. Joiner's and cabinetmaker's mortise chisels are priced the same and where shown, share an illustration. The surviving catalogs are all wholesale to the trade so it's very possible that the latter two styles are identical, but are listed separately to account for what customers were used to ordering.

In theory the bolster, the wide ring of steel at the base of the chisel where the handle butts up against and transfers the force of the mallet blow to the steel needs to be flat on the tang side so that the handle will neatly and evenly bed down into it. Some samples I own are like this, others are far rougher and flush fitting a handle without a leather washer would have been pretty hard. This could account for some of price difference.

Smith's key shows the cheaper style as having octagonal bolsters but later catalogs do not. Some of the earlier catalogs show the cheaper style with a not quite oval bolster but certainly not an octagonal one. Some catalogs show the cheaper style with a thin bolster and the "Best" with a thick one - almost double in thickness. In any case I can't see anyone paying nearly double for a cosmetic change. Thin is more elegant than thick and it's less expensive. Octagonal is harder to make than actually oval, the sort or rounded rectangles are easier still. It is far more likely that the price difference was about differences in the length of the welded on steel cutting edge, and if the edge was cast steel or less expensive blister steel. I suppose it is also possible that once you have decided to use cast steel and made a higher grade tool the fit and finish needs to be better all around. So no matter if the bolsters are thick or thin the better grade would be better ground to receive a handle. But there is no contemporary documentation that I know of that supports or refutes this.

The theory that the better chisels used cast steel is made more convincing by the 1884 James Howarth catalog. This catalog not only lists the three usual options, it also lists a version in "solid cast steel" (the price list above and the illustration below are both from Howarth) and at a much higher price, handled chisels, which were double the price of an unhandled one. You pay more for real features, not cosmetic ones.

Another point that also supports this is that bolsters of all chisels up until the mid 19th century were usually elegant octagons. Oval bolsters are easier to make because they don't need to be symmetric, but they really reflect a newer style. Considering the conservative nature of toolmakers it is very possible what we are seeing in "The Key" is a older style chisel made of blister steel by an old time maker, and a more expensive chisel made by some more modern maker using cast steel who at the same time modernized the look.

It doesn't matter. As long as the heat treat of a mortise chisel hasn't been damaged, or the chisel worn past its steel edge it will work fine.

The pricing difference between the types of chisels is typical of all the catalogs I consulted. For 1 dozen (these are all wholesale catalogs) 1/4" mortise chisels you had the following options (in shillings / pence) The pricing difference between the types of chisels is typical of all the catalogs I consulted. For 1 dozen (these are all wholesale catalogs) 1/4" mortise chisels you had the following options (in shillings / pence)

| Common Mortise | 8/3 | | Best Jointer's and Cabinet Mortise | 14/0 | | Best Jointer's and Cabinet Mortise - handled | 23/0 | | Cast Steel Cabinet Mortise | 16/0 | | London Sash Mortise Chisels | 16/0 |

Sizing (and this is important):

All the catalogs list mostise chisel widths from 1/8" to 5/8" by 1/16"s and (the early catalogs especially also list 5/8" - 1" by 1/8". Sizes over 5/8" are pretty rare, and largely useless for regular cabinetmaking. Driving a chisel that wide is hard. The reason for the 1/16" gradations, at a time when bench chisels were only available in 1/8" increments, was that the usual way of making a mortise (as documented by Moxon in 1678 but almost nowhere else) was that you would gauge the lines of the mortise to whatever size you wished, or the exact size of an existing tenon, then select the next smaller size mortise chisel. With at most 1/32" waste left on the sides, you could chop a mortise very very quickly, and not too carefully. Then a wide paring chisels, would be placed on the scribe line exactly and trivially peel off the excess to a perfectly dimensioned smooth walled mortise. The 1/8" increment of sizes available for bench chisels would leave too much waste to pare away.

While I mentioned that the very late James Howarth catalog lists handled chisels, retailers certainly offered chisels with handles to their customers all through the 18th and 19th century. Christopher Gabriel, the London planemaker and ironmonger who sold the Seaton chest (one of the very few extant nearly complete late 18th century tool chests) stocked tool handles in his inventory and the mortise chisels (by Law) in the chest are so uniform and professional and little I find it hard to believe that they were not sold to Seaton with handles originally in place.

English style mortise chisels were never made in Continental Europe or in the US. In Europe they use a heavier version of a sash mortise chisel, and in the US even very early on mortising was mostly done by machine, but tool catalogs offered imported English mortise chisels. There is a version of a socketed mortise chisel that was made in the US but I have only seen them listed in catalogs - they are not common in the wild. They are simply heavier versions of regular American style socketed chisels.

Click here for Part 3 "The Body Of The Tool".

|

Join the conversation |

|

Joel's Blog

Joel's Blog Built-It Blog

Built-It Blog Video Roundup

Video Roundup Classes & Events

Classes & Events Work Magazine

Work Magazine

The pricing difference between the types of chisels is typical of all the catalogs I consulted. For 1 dozen (these are all wholesale catalogs) 1/4" mortise chisels you had the following options (in shillings / pence)

The pricing difference between the types of chisels is typical of all the catalogs I consulted. For 1 dozen (these are all wholesale catalogs) 1/4" mortise chisels you had the following options (in shillings / pence)

A very timely review of these interesting tools. (How about part 6 on the socketed types? - even if they're more appropriate to framing or boat-building than cabinet-making).

Goldenberg's (French) catalogue of the 1920s has chisels very similar to the extra heavy duty socketed mortice and to the lighter 'pig-sticker' with a thin bolster (but very much the Sheffield type of tang) - but you're right that the common UK version was not a normal continental chisel.

Danny, Sheffield, UK.

This steel was also used for clock springs, and c 1740, Benjamin Huntsman, a clock maker, discovered that remelting blister steel in a crucible produced a homogenity hitherto unavailable - modern making steel was born, and the crucible process remained in use for over 200 years. Often known as 'cast steel', it was still used for the cutting edge only, it still being cheaper to weld it to a softer, iron, body. Edge tool makers, e.g. the Abbeydale forge in Sheffield, still made tools by this method until WW2, and in France it remained common practice until the 1980's....

It was Bessemer's discovery c 1855, and the Siemen's Martin process developed around the same time in Europe, that allowed cheap carbon steels to be produced and led to all steel tools being available - it was finally cheaper to forge the whole tool from a steel bar, than to weld on a separate cutting edge.

Despite this old methods continued, and some makers continued with welded blades well into the 20th century. New manufcturing methods, e.g drop forging, and later roller forging, soon put these old makers out of business as they were not able to compete with the newer mass production techniques. The last surviving commercial use was in making scythe blades, where the comination of a hard cutting edge and a flexible body produced a unrivalled tool - until the mowing machine and combine harvester finally nailed the coffin shut....